When each of these 10 species stand against a background of pure white snow, they’re difficult to spot: they have adapted to their extreme Arctic environment by developing white fur that allows them to dodge predators and stalk prey. Arctic foxes, wolves, ermines, seals, hares, owls, bears, sheep, tern and falcons are among the most striking wildlife that can survive in some of the planet’s most extreme environments.

Arctic Fox

(images via: em_j_bishop 1 + 2, jinterwas, will_89)

Found throughout the Arctic, Vulpes lagoons is a small fox that can withstand some of the most frigid weather conditions on the planet. The arctic fox has adapted to freezing conditions with thick fur, a good supply of body fat, hairy paws and a thick, soft tail that it can wrap around itself like a blanket. The arctic fox is gray to brown in warm weather, and turns white in the winter to help it blend in. It survives by hunting lemmings, voles, hares, owls and the eggs of birds. Unfortunately, this beautiful species is being crowded out by the more common red fox due to climate change. As less of the Arctic is covered in snow for much of the year, the arctic fox’s white coat loses its camouflage value.

Harp Seal

(images via: carola, wikimedia commons, national geographic)

Once these little harp seals reach adulthood, they’ll look very different. Harp seals start out with a yellowish white to pure white coat that helps protect them from predators, but grow into mottled gray coats with a concentration of black coloring on their faces. The backs of adults are covered in black harp or wishbone-shaped markings, hence their name.

Harp seals not only keep warm with their thick coats of blubber, but with the help of their flippers, which act as heat exchangers. Their eyes always have a moist, watery look thanks to a coating of tears that protects them from salt in the water.

Each year outside of breeding season, the harp seal population – which is split into three geographic groups in various parts of the arctic – moves up to 2,500 miles northeast.

Arctic Hare

(images via: wikimedia commons, i love greenland, emma bishop)

Snow-white arctic hares follow their twitching little noses to the few bits of plant matter that can be found in the Arctic during cold weather, sometimes digging for willow twigs and roots. The largest hare in North America, Lepus arctics has grayish-brown fur in the summer that turns white for winter, except for the tips of its ears, which are black. They’re able to hop on their hind legs like kangaroos at up to 30 miles per hour, which is a good thing when they’re trying to outrun fearsome predators like the arctic ermine, arctic fox and snowy owl.

With populations concentrated mostly in Northern Canada, arctic hares are nocturnal and gather in groups of 10-60 when feeding. They dig holes to sleep in and will sometimes pile up in large numbers to stay warm, but are often solitary.

Arctic Wolf

(images via: tsaiproject, jason langlois, purplegothicqueen, milestoned)

When their coats turn white for winter, Arctic wolves are even more striking than their warmer-weather counterparts. Outside winter, these wolves have gray-brown coats, but they also have more rounded ears, shorter muzzles and shorter limbs than other wolf subspecies to reduce heat loss in extreme temperatures. They inhabit the Canadian Arctic, Alaska and the northern parts of Greenland on remote tundras where prey is limited. Because food isn’t readily available, Arctic wolves have a range of about 1,000 square miles.

Their insulated fur helps them withstand temperatures that drop as low as -70 degrees Fahrenheit and can survive in total darkness for five months out of the year. Arctic wolves travel in packs of 2 to 20, and live in small family groups. Their prey includes caribou, muskoxen, arctic hares, seals, lemmings and birds.

Snowy Owl

(images via: wikimedia commons 1, 2, 3; ross elliot, dazzie d)

The scalloped black -edged flowers of the Snowy Owl slowly disappear was winter sets in, making them almost entirely white. Snowy owls are closely related to horned owls and have ear-tufts, but they’re small and usually tucked away, so they’re not noticeable. These winged predators are among the largest species of owls with wingspans reaching 59 inches in width. Known to be nomadic, snowy owls adapt to variations in prey availability, sometimes living below the Arctic circle for access to good hunting areas.

The Snowy Owl primarily preys upon lemmings and other rodents as well as larger mammals like hares, raccoons and marmots, but will also eat juvenile ptarmigans (a species of grouse) and other birds.

While Snowy Owls have few predators, they have to defend their nests fiercely against arctic foxes, corvids, dogs and gray wolves seeking eggs and vulnerable young.

Polar Bear

(images via: flickr favorites, travel manitoba, irish wildcat, wikimedia commons)

The most iconic symbol of Arctic wildlife, the polar bear is a strong swimmer living in one of the earth’s coldest environments. With webbed feet that they use as flippers in the water, polar bears can swim hundreds of miles from land, occasionally catching a ride on a floating sheet of ice. This beloved species is increasingly at risk due to climate change, as ice in the Arctic melts at alarming rates. Eight of the nineteen species of polar bear sub-populations are in decline.

Under all that thick white fur is black skin that allows the polar bears to soak up warmth from the sunlight. They have fur on the bottoms of their paws to protect themselves from the ice, and large claws that not only help them hunt but also enable them to dig deep into snow drifts to create dens.

Polar bears can reach an astonishing 1,600 pounds and up to eight feet in length. On all fours, they’re as tall as an average adult male human. This makes them the larger terrestrial carnivore in the world. They use their sense of smell to locate seal breathing holes in the ice and wait silently nearby for the faint sound of a seal exhaling. Then they reach into the breathing hole and drag the seal out onto the ice. Polar bears also eat fish, bird eggs and young, walruses, whale carcasses, muskox, reindeer, rodents and crabs.

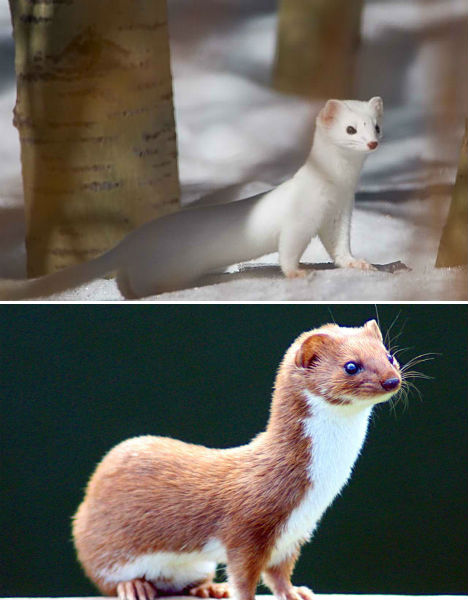

Arctic Ermine

(images via: tundra animals, wikimedia commons)

‘Arctic ermine’ sounds a lot prettier than this animal’s other common name, the short-tailed stoat. This particular subspecies of weasel is best known for its super-soft, winter-white pelt, but it’s every bit as fearsome as its relatives. Living in the coldest biome in the world, the arctic ermine is yet another animal that changes color to match the snow, its coat a rusty shade of red-brown in warmer weather.

Though it’s very small, the arctic ermine has very sharp teeth that enable it to capture prey larger than itself. A tenacious predator, this species has been known to kill animals even when it’s not hungry – seemingly just for sport. It eats mice, lemmings, squirrels and small birds as well as rats and rabbits. Blending into the snow, it uses the black tip of its tail to draw in unsuspecting birds who assume it’s an insect of some sort.

Dall Sheep

(images via: karina y, wikimedia commons, scubadive67, wikimedia commons, y entonces)

Dramatic curving horns are the most notable feature of Dall sheep, a species native to northwestern North America that are almost entirely white in color. They’re primarily found in the subarctic mountain ranges of Alaska, the Yukon territory, the MacKenzie Mountains and the Northwest Territories.

Many of them are sheltered within the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in Alaska. Year-round residents of the Refuge, Dall sheep live high on ridges and steep mountain slopes, using the rugged terrain to escape predators like wolves, golden eagles, bears and humans. These herbivores have adapted to the scarce food availability their frigid environment by maturing slowly, with low reproductive rates, to save their energy.

According to the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, “Dall sheep walk a survival tightrope, although they do it rather effectively. They have lived since the Pleistocene in places such as the Arctic Refuge.”

Arctic Tern

(images via: kitty twerwolbeck, cams & backpackers, elma)

With an annual migration covering 44,300 miles – the longest regular migration of any known animal on earth – the Arctic Tern certainly gets around. It goes from the Arctic circle as far south as Massachusetts over the course of the year. Mostly gray and white with black crowns and red beaks, Arctic Terns are medium-sized birds with wingspans of about 30 inches. Many of them can live up to thirty years.

Each individual tern has its own special social call that is distinguishable to the other terns, allowing them to identify individuals. They mate for life in most cases and will defend their nests fiercely against predators, even attacking humans by striking the top or back of the head with their beaks.

Arctic Gyrfalcon

(images via: andrea pokrzywinski, rebeccakoconnor 1 + 2, emma bishop)

The Gyrfalcon is the largest of the falcon species, and breeds all over the Arctic coasts of North America, Greenland and Northern Europe. Its plumage varies greatly from dark brown and black to almost solid white. White form Gyrfalcons are the only predominately white falcons in existence, and tend to be located in Greenland.

Gyrfalcons breed fuzzy white nestlings on bare cliffs, often in the abandoned nests of other birds like ravens and golden eagles. They’re very aggressive toward any creatures that come too near their nests, dive-bombing brown bears. Their primary threat is humans, mostly in the form of either car collisions and hunting. They can live to be up to 20 years old. While the species was considered ‘near-threatened’ from the mid-20th century to 1994 due to poisoning from pesticides, they have since made a comeback, and are no longer considered rare.